Becoming the baddies…

How to write from the ‘wrong’ side of the story.

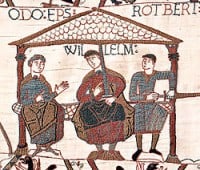

As I start to pull together my research on the Normans ready to launch myself into the third book of my trilogy, I find myself with a very interesting task - learning to love the enemy. In this case, William the Conqueror.

As I start to pull together my research on the Normans ready to launch myself into the third book of my trilogy, I find myself with a very interesting task - learning to love the enemy. In this case, William the Conqueror.

My first book, The Chosen Queen, is written from the Saxon point of view, so clearly Duke William is very much the evil one, nicking England off the English at the Battle of Hastings. In Book 2, The Constant Queen, written from the Viking point of view, William is more at the fringes of the story but is still very much the ‘jumped up Norman’ who will have to be disposed of to take England. Now, though, with Book 3, The Conqueror’s Queen, telling the story of William’s wife, Matilda, I am having to look at the conquest of England in a whole new light and it’s fascinating.

As a writer I have always loved the idea of ‘the other side of the story’ and am always fascinated by books/films/plays that take a well-know tale and look at it from a new angle (the nativity from the donkey’s point of view is your primary school classic, Hamlet through Ophelia’s eyes, or Robin Hood through King John’s – that sort of thing). I am, therefore, very much up for the challenge of approaching 1066 from the other side of the channel, but it’s also quite hard. I’ve spent two writing years regarding Duke William as the devil incarnate, so to get under his skin is a little, well…. itchy. That said, it’s starting to happen and this is where I find research so fascinating. Immersing yourself in the details of someone’s world will always have the effect of levering you just a little bit inside their mind too. The story of William’s Normandy up to 1066 is one of a courageous young duke (very young – he acceded aged only 8) fighting to keep his duchy intact against hostile invaders and to try and modernise it with both governmental and ecclesiastical reform.

What emerges is a man of huge energy, diligence and vision and those are all remarkably attractive qualities. What also emerges is a man who genuinely believed he had been promised England, however tenuously, and who saw his invasion as almost as much a defence of his rights as his endless repelling of rebellions and invasions in Normandy in the preceding 20 years. Even if it is still hard to truly love such a ruler, it is impossible not to admire and understand him and I am enjoying seeing the man I wish to write about emerge from the facts.

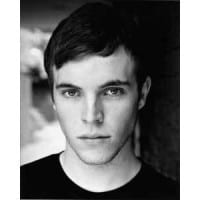

This process has also been helped by the rather more frivolous discovery of a ‘face’ for my William – that of the totally gorgeous, brooding Tom Hughes, who I discovered as Joe Lambe in the excellent recent BBC drama The Game. Imagine, if you will, this man (pictured left), with his sculptured cheekbones and dark, piercing eyes, in rich Norman armour, skilfully commanding a powerful warhorse and maybe it is not so hard to love this man – or at least to fancy him!

This process has also been helped by the rather more frivolous discovery of a ‘face’ for my William – that of the totally gorgeous, brooding Tom Hughes, who I discovered as Joe Lambe in the excellent recent BBC drama The Game. Imagine, if you will, this man (pictured left), with his sculptured cheekbones and dark, piercing eyes, in rich Norman armour, skilfully commanding a powerful warhorse and maybe it is not so hard to love this man – or at least to fancy him!

So what of his wife, Matilda of Flanders? The wonderful thing about writing my trilogy from the point of view of the relatively unknown wives, is that I do not have to view these warrior kings through my own eyes but through theirs. One of the big battles for the historical novelist is to try and see their period as it was seen at the time. No one, for example, however tempting it might be to have them say so, thought ‘oh if only we had a big machine that could compute numbers’, or ‘a device that could let us talk to people on the other side of the world’ or even ‘a way of heating the further reaches of our homes’.

It is fun to chart the arrival of inventions we now take for granted – glass in windows, for example, was the ‘in new thing’ amongst rich Saxons – but I think it’s also important to remember that every era thinks of itself as ahead of the last and is far quicker to spot its improvements on times past, than the potential gaps that might be filled in the future. We humans will always see ourselves as on the cutting edge of technical and cultural advancement and William’s Normans must have considered themselves very lucky to live in a time of such relative peace and prosperity, largely as a product of his force of personality and power. Matilda must, therefore, have been very proud to be his wife, whatever the nature of their personal relationship.

On this point, however, I am lucky, for personal relationships is one area that is largely the historical novelist’s to decide upon. There is very little evidence of anything as ethereal as feelings from this period, or indeed from any period until the advent of the celebrity cult in only the last century. Notable exceptions to the general marital rule of ‘muddling along well together’ are always recorded and William’s is one such. He is reported, without exception, as having been faithful to Matilda – a fact that is deemed so hugely noteworthy to contemporary chroniclers as to suggest how very unusual this was amongst the richer men of the age. It suggests both discipline and, we would hope, a certain level of genuine affection for his wife and the mother of his nine children.

William seems to have been grief-struck at Matilda’s death and throughout their life together, chroniclers (occasionally) saw fit to pass comment on the apparent happiness of his and Matilda’s union. Given the vast differences in their upbringings – his as a warrior duke, having to fight every step of the way just to hold onto his title, and hers as a privileged, educated and cultured princess in a stable and diverse court – this is intriguing. It seems to me a rich contrast and one I intend to explore in the way I know best – fiction. Bring on the baddies….

THANKS FOR READING

Want to stay in touch?

Do say hello on Twitter

or join my mailing list for regular news and offers

Hope to see you soon - Joanna