Fab historical writers – James Aitcheson

I first met James Aitcheson at the Battle of Hastings re-enactment three years ago. At the time I was writing The Chosen Queen, exploring the Saxon side of 1066 so felt very much on the 'opposite side' of James and his Norman hero Tancred. I loved his books but struggled to embrace Norman Britain. Since then, however, I have come to write The Conqueror's Queen, told from the viewpoints of Mathilda of Flanders and William the Conqueror, and have embraced my inner Norman! It was a huge pleasure, therefore, to see James again at last year's 950th anniversary re-enactment and to 'talk Norman' with him and I am delighted to feature him on this blog after his latest excellent novel, The Harrowing, came out in paperback last week.

I first met James Aitcheson at the Battle of Hastings re-enactment three years ago. At the time I was writing The Chosen Queen, exploring the Saxon side of 1066 so felt very much on the 'opposite side' of James and his Norman hero Tancred. I loved his books but struggled to embrace Norman Britain. Since then, however, I have come to write The Conqueror's Queen, told from the viewpoints of Mathilda of Flanders and William the Conqueror, and have embraced my inner Norman! It was a huge pleasure, therefore, to see James again at last year's 950th anniversary re-enactment and to 'talk Norman' with him and I am delighted to feature him on this blog after his latest excellent novel, The Harrowing, came out in paperback last week.

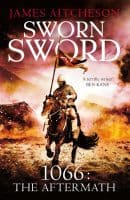

All four of James' novels are set during the Conquest, amidst the violence and chaos of the years immediately following the Battle of Hastings. Sworn Sword is the first volume in the Conquest series, featuring the Norman knight Tancred and charting his quest for vengeance after his lord is murdered by English rebels. Originally published in 2011, it has since been followed by two sequels, The Splintered Kingdom and Knights of the Hawk.

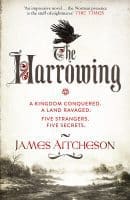

As mentioned above, James' latest novel, The Harrowing, is out now in paperback, published by Quercus. Set in 1070 during a particularly brutal phase of the Conquest known as the Harrying of the North, it centres upon five English refugees – a priest, a lady, a maidservant, a warrior and a poet – who band together for survival as they flee the devastation of their homeland by the Normans. None of the five, however, is quite as innocent as they first seem: each is hiding a dark secret. As their enemies close in, one by one they’re forced to confront their pasts in order to find redemption before it is too late.

James' novels are meticulously researched and written and I highly recommend you seek them out, but first a little about him as a writer:

What’s your favourite thing about being a writer?

What’s your favourite thing about being a writer?

Many writers will say that the best thing about their job is when they finally come to hold their finished book in their hands. For me, though, it’s about the journey, not the destination. The act of creation is everything: I love striving to craft the perfect sentence or paragraph, weaving plot threads together, and the feeling of completeness that results.

In particular I find the editing process extremely rewarding, because that’s when a novel really takes shape. Taking the raw material of the first draft and refining it; pruning any unnecessary growth; squeezing out the very best that the narrative has to offer: that’s when I get greatest satisfaction.

And your least favourite?

Writing is a solitary occupation: you have to be comfortable spending long stretches of time by yourself, lost in your own thoughts. I’m a social person by nature, so I find this aspect of the writer’s life the most difficult.

Writing is a solitary occupation: you have to be comfortable spending long stretches of time by yourself, lost in your own thoughts. I’m a social person by nature, so I find this aspect of the writer’s life the most difficult.

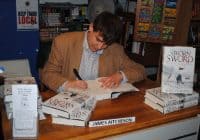

To escape my desk, I make a big effort to get out and speak to other people – fans, fellow authors, historians – at festivals, conferences and other events throughout the year. I’m also a founding member of a writers’ circle that’s been meeting for the past nine years. Every month we get together to give feedback on each others’ works-in-progress, drink copious amounts of coffee and eat cake. That kind of support network is, I think, essential for any writer.

Why were you drawn to the Normans?

The story of the power struggles of 1066, culminating in the famous Battle of Hastings, is generally quite well known, but what followed is less so. The Norman Conquest was a time of intense and profound change in England: of social, cultural and political upheaval on a scale that I think is difficult for many of us to imagine nowadays.

The years after 1066 saw the native Anglo-Saxon elite expunged and replaced by a French-speaking aristocracy who instigated a revolution not just in language, law and culture, but also in the landscape itself. The kingdom was carved up into new territorial divisions, and castles were built to dominate both town and country.

I’m fascinated by what it must have been like to live through such momentous and traumatic events. Even after four novels, and thirteen years of studying the Conquest in one form or another, I feel I’ve barely scratched the surface of this rich and complex period.

Are there any other periods in history you fancy tackling?

I continue to be fascinated by late Anglo-Saxon and early Norman England, and see myself exploring it for some time to come. If I were to venture beyond that comfort zone, though, I might be tempted to explore late antiquity, and in particular the end of Roman Britain: another favourite period of mine, which I studied in-depth during my time at Cambridge, and which also – like the Norman Conquest – witnessed considerable social and political transformation.

What do you think is the appeal of historical fiction?

What do you think is the appeal of historical fiction?

Historical fiction is such a wide-ranging genre, and comes in so many different varieties. that it’s hard to make sweeping generalisations about why it appeals. I can only really speak for myself: why I enjoy writing it, and why I’ve chosen fiction rather than history as my medium.

Fiction’s great strength, in my view, is its ability to put us in the shoes – and in the minds – of others. By giving us access to unfamiliar, dissenting and sometimes uncomfortable points of view, it can dispel myths, challenge our preconceptions, allow us to interpret events in a new light, and so lead us to new understanding.

All of my novels have explored this theme to some extent, but it really comes to the fore in my latest novel, The Harrowing. My five protagonists aren’t shapers of events – they aren’t kings or queens or lords – but rather ordinary people drawn from the margins of history, caught up in a crisis not of their making, responding to and trying to come to terms with a world beyond their control.

These are the sorts of stories that seem to me most worthwhile exploring. Historical fiction can give voice to these marginalised individuals. Imagining and engaging with their thoughts and feelings helps remind us that the past is still close, and that the struggles, conflicts and dilemmas faced by people long ago are not so different from those experienced by many today.

If there was one thing in history you could change what would it be?

Nothing. If I’ve learnt anything from time travel films, it’s that you should never mess with the past!

James chatting with readers at the Battle of Hastings re-enactement

You can find all James' books on Amazon and connect with him via his website, twitter, or facebook ,or listen to his podcasts on soundcloud. Feel free, too, to pop along to my facebook page to comment on this blog.